From chapli kebabs to persian sherbets: Why Karachi’s Café 1947 feels like home

Walk into Café 1947 in Badar Commercial in Karachi’s DHA and you feel the room exhale. The hum is low, the lights are warm, and hints of Persian ornaments — patterns, textures, a soft palette — signal a space that values detail over display.

Children from the family running the eatery drift in and out of the room, the sort of gentle punctuation you only get in a home. Plates don’t arrive in a hurry; they appear one by one, as if the kitchen were composing a conversation rather than completing an order. The result is a meal that feels unhurried and deeply personal.

“We wanted a space that reflects the culinary ethics and aesthetics of the past,” says Aemal Zahra, Café 1947’s social media manager, explaining the name’s evocative pull without making it a Partition reference.

“Café 1947 stood out for its simplicity and imagery… it quickly evokes associations between the café, the past, and cultural heritage. When my mother first suggested it, we felt it was reminiscent of the literary café culture Pakistan had in its early years.” It’s an intelligent choice, historically resonant but roomy enough to hold multiple meanings.

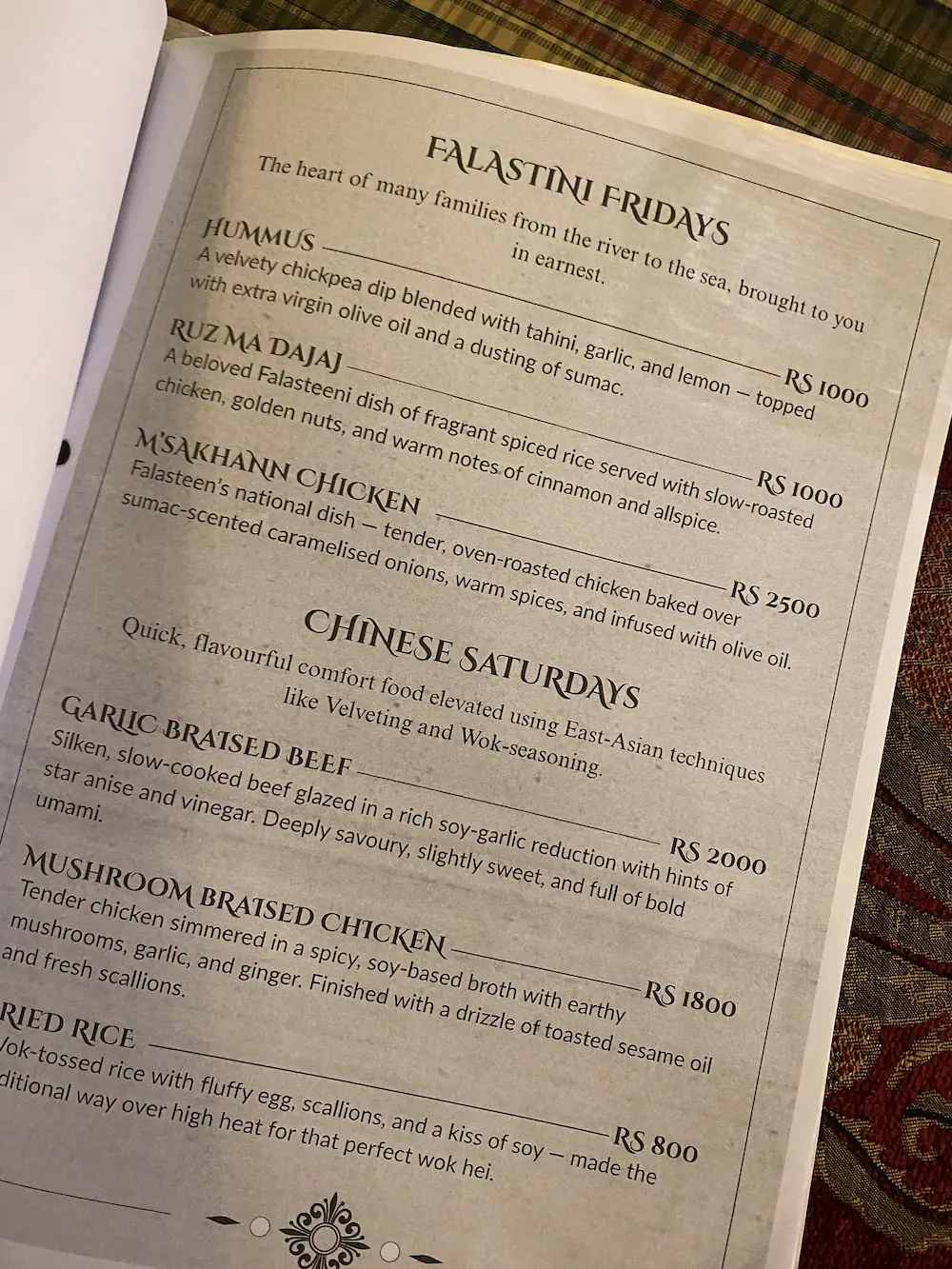

Café 1947 calls its repertoire pan‑eastern, but that label undersells the curation. The kitchen is helmed by Asiya, Aemal’s mother, who spent 15 years as a flight attendant and, more importantly, a lifetime as a dedicated cook and reader. The menu’s compass traces the old Silk Route with lived-in specificity: Afghani Mondays, Iranian Tuesdays, a Pakistani Wednesday heavy with memory, Mughlai Thursdays, Falasteeni Fridays, Chinese Saturdays, and a nostalgic Russian Sunday.

“The concept was inspired by our kitchen at home,” Aemal tells me. “We wanted to deliver the best and most perfected of our recipes. These were dishes from across Asia we’d been enjoying at home for years.”

To keep the workload humane — because these dishes are labour-intensive — the family set up a rotating menu. Each theme focuses on three key dishes.

Some recipes are ancestral — nargisi koftay and galawati kebab — while others are shaped by travel, like their beef stroganoff, a wink to an old Saudi Arabian Airlines classic. Some are hybrids born of journeys and friendships: a Herati‑style mutton rosh learned at night in hostel kitchens; chelo kebab refined after living with a local family in Iran’s northeastern city of Mashhad.

My favourite? The chapli kebab. It is the dish that first makes you sit up in your seat in anticipation. It lands with a sizzle and a promise, its edges coppery and crisp, the beef coarsely ground so the spices have room to speak. It’s the best I’ve had in a while — bold, clean heat that doesn’t bulldoze the palate, the sort of balance you only achieve when the hand knows when to stop.

If the kebab is bravura, the Baked Chicken is restraint perfected. Brined in clove and tea, marinated in a roasted-pepper blend, then eased into the oven till tender, it’s a plate that makes Nando’s feel like a distant memory. The meat holds together but yields instantly, and the saffron rice served with it is fragrant without being perfumed to distraction. There’s craft here, but also tenderness.

For something quieter, the Baked Chicken Pita Pockets offer exactly the simplicity the café promises: soft khubz, tahini and olive oil, crumbled feta, onions and tomatoes; nothing showy, everything intentional. It tastes like a weekday dinner in a good home, the kind that restores you.

And then there is Mutton Rosh, a broth that speaks in low, velvety tones. Potatoes and green peppers provide company to slow‑cooked mutton that practically sighs off the bone. It’s comfort food, yes, but also travel food — the kind you imagine eating with friends in a foreign city after a long day. A bowl that teaches you that familiarity is not the enemy of depth.

The drinks roster reads like a memory book. Qamar al‑Din, the amber apricot nectar of the Levant, is so fresh and faithful it transported me straight to Hunza, where I once drank something nearly identical amid orchards and mountains. Serkanjebin, the ancient Persian mint‑vinegar sherbet, is precise and refreshing, tuned for Karachi’s often oppressive heat. Neither drink is saccharine; both carry the discipline of older kitchens.

For dessert, the chocolate buns, puffed Japanese‑style milk buns with generous helpings of chocolate, arrive bearing hand‑drawn faces of lions. It’s whimsy, yes, but executed with a confident hand: enough chocolate to make the point, not so much that you regret it. They’re the sort of sweet that makes the table smile.

Part of Café 1947’s quiet genius is its rotating weekly sofra. Each day ushers in a new three‑dish focus that keeps regulars returning without turning the kitchen into a carousel of compromises. Afghani Mondays might bring Namkeen Boti, Mutton Rosh and Kabuli Pulao; Iranian Tuesdays exit the grill with Kebab Koobideh and Chelo Kebab; Pakistani Wednesdays revisit Sindhi Biryani, Galawati Kebab, or a grandmother’s Purani Dilli Biryani without the perfumed excess that sinks lesser versions. The point isn’t breadth — it’s attention. Aemal frames it crisply: “The rotation creates novelty for guests while honouring how labour‑intensive these dishes are.” It’s also an editorial stance: each service reads like a well‑curated issue.

Ask what best represents Café 1947 and Aemal doesn’t hesitate: Ghutwa Kebab, a cherished Awadhi preparation. “It is a unique, finely minced meat cooked slowly into a paste‑like consistency rather than being shaped and grilled. The slow‑cooked process and roasted homey spices reflect the complexity of flavour we bring. There’s nostalgia too: Ghutwa Kebabs have been made by our foremothers in Majalis for generations.” It’s an answer that doubles as an index of the café’s values: patience, technique, memory.

There’s a small but telling rhythm to how things move at Café 1947. Because the family cooks and serves, plates arrive sequentially. The pacing is gentle, not sluggish; it allows you to finish a thought, notice a spice, register a texture. In a city addicted to speed, this cadence feels like a manifesto.

The team plans to expand both space and menu in the coming year. Expect Kashmiri, Gilgiti, and Pan‑Arabian additions to the sofra, and for winter, a suite of soups; pumpkin, carrot, mushroom, lentil, that sound tailor‑made for Karachi’s brief but beloved cold season.

Why go? Because the food is cooked like someone cares whether you ate well today. Because the menu travels without losing its accent. Because in a room with Persian hints and family chatter, Karachi feels connected again to a larger, older map.

Café 1947 doesn’t shout. It simmers. And that, perhaps, is its most contemporary gesture. Every day is a new meal, which is to say every visit is an invitation to return.